By Francesca Lupia

Connecting people with stories is a journalist’s job – and it’s almost never as easy as it sounds.

Identifying reliable sources and reaching broad audiences are challenging tasks, especially when covering “untapped” communities that have little experience in the media spotlight. Interacting with such populations requires time, skill, and, in some cases, an entirely new approach to journalism.

From October 16 to 18, 2015, newsroom leaders from across the country met on Stanford University’s campus for the annual American Society of News Editors – Associated Press Media Editors (ASNE-APME) conference. In a featured panel entitled “Flip It! Disruptive ways to engage untapped audiences”, three editors shared their experiences with “flipped” narratives – community at the center – and community engagement. Intrigued, I reached out to the editors after the conference, hoping to expand upon the panel’s productive discussion. In a series of interviews, all three editors offered detailed discussion and advice, providing fresh insight into their methods and takeaways.

The editors hailed from diverse locations and backgrounds:

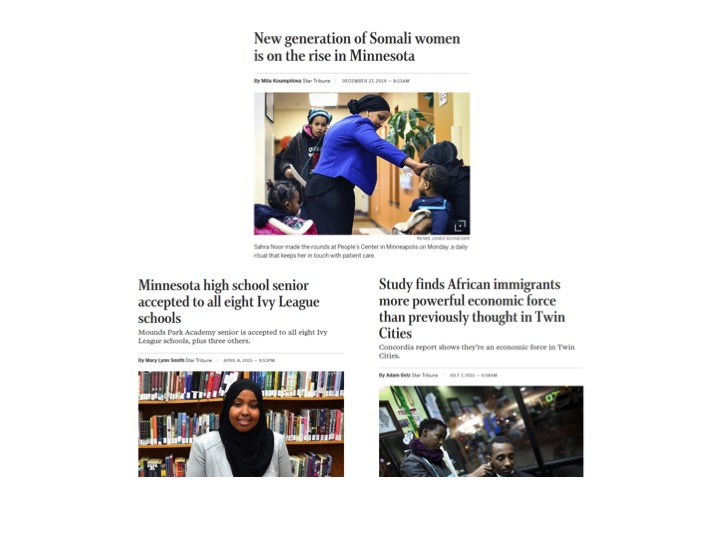

- Suki Dardarian, managing editor of the Minneapolis Star Tribune, reflected on her newspaper’s coverage of Somali-American refugee communities in the Twin Cities area.

- Gilbert Bailon, editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, shared insights gained by covering communities of color in Ferguson and greater St. Louis.

- Alfredo Carbajal, managing editor of Dallas-based daily Spanish-language publication Al Dia, discussed the steps he and his colleagues take to provide nuanced coverage of immigration issues and Mexican-American communities in Texas.

In this set of suggestions for editors seeking to reflect diverse perspectives through community engagement, the editors share their thoughts on powerful, people-centered journalism. Here are three themes (Educate, Empathize, and Engage) to keep in mind when embarking on an endeavor in “flipped” journalism:

Educate (both internally and externally).

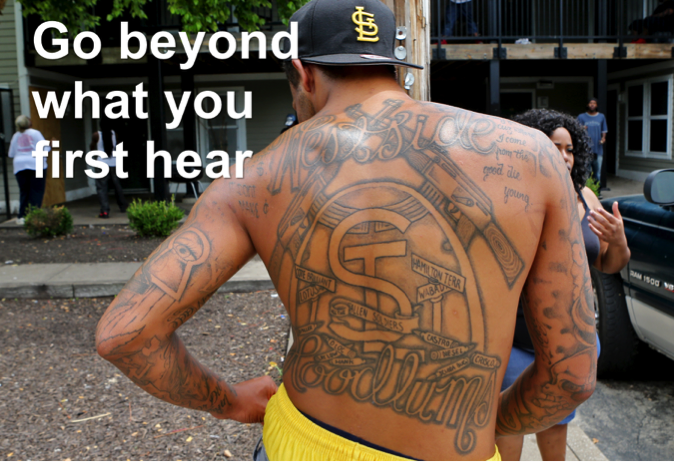

At its core, journalism is about disseminating information in a way people can access and understand. “Flipping” the narrative may add several additional layers of difficulty to this task, from language barriers to distrust of organized media. On the editorial side, lack of information may also pose problems; in some cases, extra staff training or discussion will prove invaluable to understanding a community’s complex dynamics. Gilbert Bailon and Alfredo Carbajal weighed in on what editors can do to ensure that sources, reporters, and writers are as informed and educated as possible:

- Be prepared to deal with suspicion and inexperience. Non-traditional sources are rarely what Alfredo Carbajal calls “media-savvy.” They may be nervous or disorganized when dealing with media – and in some cases, they may feel that your news organization is in cahoots with hostile forces. Although such perceptions can be difficult to dissuade, simple one-on-one conversation goes a long way. If a person feels that they can trust your organization to tell their story with accuracy and sensitivity, if they feel that their voice is being respected, information may start to flow, even if the interaction was initially hindered by miscommunication or distrust.

- Continue the conversation, inside and outside of the newsroom. Schedule frequent meetings with key sources, and follow up to build trust and ensure that you’re not missing valuable information. Alfredo Carbajal thinks that a relentless effort to cultivate new sources help to create a “culture of discovery” that leads to finding stories that oftentimes are not obvious on the surface. “Reporters, when interviewing sources, should go beyond asking ‘How do you know about this?’ but also ask, ‘Who else knows or has a stake on this issue?’” he said. “This could lead to the discovery of new dimensions of the story.”Education within the newsroom is another vital component of this culture. This effort may take the shape of official training or professional development sessions. It can also consist of more informal dialogue and discussion. Constant communication around sensitive topics helps both editors and reporters get up to speed.

- Broaden (and deepen) your source base. Well-established “traditional sources,” such as law enforcement, government officials, or business leaders, are often easier to interact with than community members – and indeed, such figures are important sources of information. But seeking sources outside official channels is essential to high-quality and comprehensive journalism. After establishing a broad, representative source base, editors should strive to maintain deep, trust-based connections with community members. Gilbert Bailon emphasized the importance of following up: “You can always go back and dig deeper. Most stories won’t just be a one-shot deal.”

- Rethink your assumptions. When dealing with sources from underrepresented populations, Alfredo Carbajal has crafted a new “golden rule” for his newsroom: “Never assume.” Especially when dealing with untapped or unfamiliar communities, misinformation is hard to avoid. Through continued and committed conversation with your sources, dedicate yourself to deconstructing preconceptions. Additionally, give careful consideration to the way you name and frame your coverage. Your headlines, however carefully crafted, may no longer accurately reflect a story’s content after new information comes to light. Always be on the lookout for bias and inaccuracy, and strive to use your newfound connections within the community to build a more reflective, resonant story.

Empathize (in reporting and research).

The skill sets required to interact meaningfully with underserved communities extend beyond research chops and reporting savvy. One crucial purpose of “flipped” storytelling is providing marginalized people and populations with the humanity they deserve (and are often denied). All three editors offer their advice on empathizing and connecting with untapped sources:

- Listen. This may seem like obvious advice; after all, editors and journalists are in the business of searching out stories. But engaging with untapped populations requires honesty, transparency, and genuine interest. In the words of Suki Dardarian, “You might have to have a lot of conversations without the notebook before you can even start doing interviews.” When interacting with potential sources, keep an open mind and focus on building mutual trust and respect.

- Invest time in understanding your community. For reporters, spending time on research and source development is an essential investment. Understanding the context of a community is an integral step of nuanced, informed, and interesting journalism. Alfredo Carbajal stressed that making more time to engage with the communities you serve shouldn’t be seen as a waste of time; rather, “it’s an investment in more accurate coverage.”For editors, too, stepping out of the newsroom and into the field should be a crucial habit. “We need to go out, we need to meet, we need to mingle, we need to understand, to ask questions,” Carbajal said. Good editorial leadership, he notes, requires a nuanced and accurate understanding of the local climate – and that understanding, in turn, sometimes requires editors to hit the streets.

- Seek out diversity of many kinds – and for the right reasons. All three editors agreed on the importance of building a diverse newsroom. “Different reporters have different abilities to access information and communities, and I think diversity is a big part of that,” Gilbert Bailon said.Hiring reporters and editors from diverse backgrounds, Suki Dardarian said, can help “crowdsource” the process of finding stories, and may help people in underrepresented communities feel more comfortable engaging with the media. “Having a diversity of reporters team up on one story not only can help cover more ground faster; it can also broaden and deepen the story,” Dardarian said. “Each reporter brings their background, skills and perspective, and that can’t help but make the story a richer one. In the end, it also means that we have a greater number of folks in the newsroom who understand the nuances of the community and the story.”Carbajal stressed that diversity in news and newsrooms is part of the discovery process. Inclusiveness, he said, should be about promoting fairness, accuracy, and fresh perspectives – not about numbers and quotas. “We often see diversity in news as a racial or ethnic fault line,” he said, but this perspective can obscure the true purpose of “flipping the narrative” and engaging with untapped communities. “There are many other factors for which people feel underrepresented,” Carbajal said. “I think we need to do a much better job of going beyond the obvious. “

- Emphasize impact. Humanize your coverage. “Flipping the narrative” to include more coverage of and input from untapped communities is, at its core, an effort to give journalism a human voice and face. As Gilbert Bailon’s editorial team seeks out new stories, they focus on finding individual narratives. “Instead of ‘Here’s a policy matter’ or ‘Here’s a change in how the police are going to handle things,’ we ask, ‘How does this affect people’s lives?’” Bailon said. Of course, hard facts and figures are still essential to good reporting. But a more intimate, personal approach often resonates more strongly with audiences, especially if they see stories or communities like their own reflected on the page or screen

Engage (with audience and communities).

An editor’s task here is twofold: engaging with communities that may seem nebulous and hard to penetrate, and effectively engaging with audiences. In both cases, be flexible, open-minded, and eager to try out new and innovative methods of story-gathering and storytelling. Dardarian, Bailon, and Carbajal share their tips for engagement here:

- Look for leaders. In a breaking-news setting, conflicting narratives and interests can make it difficult to pin down reliable authorities. To identify community leaders, spend time at key local events and places, and speak to people from a variety of backgrounds and organizations. Some leaders are more obvious – elected officials, health professionals, organization presidents. These sources are often good “entry points” into a local community. But leadership can also come from seemingly regular people, and the everyday expertise of teachers, relatives, and religious leaders can be invaluable in researching a story.

- Allow sources to tell their stories in their own words. Skilled journalists can portray individual stories with great sensitivity, but nobody tells a story as well as its subject. The Minneapolis Star Tribune has received widespread praise from its readers for a series of op-eds by Somali-Americans in the Twin Cities area. “Handing the mic over,” in Suki Dardarian’s words, allowed community members to take control of the narrative and inform others about their lives.

Different media platforms can also be instrumental in conveying diverse perspectives. For Gilbert Bailon, the raw, direct quality of video coverage has been an effective way to capture sources in their own words. “Sometimes people are just better talking in their own formats,” he said.

- Don’t be afraid of social media. Both as a channel for audience outreach and as a network of potential sources, social media can be an invaluable resource. The lack of fact-checking on Twitter necessitates some extra work from the editorial end. But particularly in breaking-news situations, or when engaging with communities that do not typically rely on mainstream media outlets for their news, social media is an excellent place to find background information and get a glimpse into the minds of community members.

Exploring different media platforms is key to connecting with broad audiences. Suki Dardarian has found success in employing a variety of formats in her newsroom: “We would post trailer videos on social media before story releases, which generated a lot of interest. It allows us to tell the story in different ways.” Consider photography, multimedia, video, interactive storytelling, and social media involvement when determining how to present your coverage.

- Listen. This tip bears repeating both because of its importance, and because listening in a community engagement context goes beyond seeking stories. Especially when employing a model of journalism that relies on personal connection and storytelling, listening to audience feedback is crucial. Use reader comments, letters to the editor, and online metrics as indicators of how effectively your content is reaching readers.

This guide is not, of course, foolproof. Not every “flipped” story will be an overnight success. But content that reflects readers’ situations can draw new readers and inspire action. “I think that readers want to see things that affect them, whether directly or indirectly,” Gilbert Bailon said. “It’s a more human approach to journalism.”

***

Related Stories:

“Flip it!”: Diversity, Community, and a New American Journalism

Feedback from the “Flip” Side: The Impact and Reception of Community-Centered Journalism

***

Francesca Lupia is a freshman at Stanford University with a long-standing interest in innovative and socially conscious journalism. Originally from Ann Arbor, MI, Francesca was a volunteer writer and editor for Groundcover News, a local street newspaper, for four years. At Groundcover, a small independent publication focused on homelessness and social justice, Francesca contributed articles, worked closely with low-income and homeless vendors, and developed a passion for journalism that uplifts and empowers typically unheard voices.

At Stanford, Francesca plans to major in linguistics and political science and writes for the Stanford Daily’s University/Local News beat. Bilingual in English and Mandarin Chinese, Francesca is particularly interested in US-China relations and Chinese press restrictions, and hopes to pursue a career in print journalism or law (preferably based in China) after graduation.

These stories are made possible through a joint project of Journalism That Matters and the ASNE Diversity Committee.